After two weeks at

Rock Bottom Ranch, I have seen lives end, and new lives begin. High dramas have played out at the hog pen and pasture. Laura Jean, our noble sow, gave birth to her second litter recently. And she lost two from her first litter to the butcher's rifle. The seven-month-old pigs, who had already grown to around 150 pounds, went down instantly at the gunshot, and into the death throes. They have already become sausage and ham. Hence, the food chain, in all its wonder and cruelty. Although I dread to see an animal die, I acknowledge that a grass-fed pig from one's backyard is a protein-rich foodstuff, with a markedly low ecological footprint. And I am glad to see the animals lead happy lives, in the sunny pasture, by the willow trees, against the backdrop of the snow-capped Basalt Mountain.

Laura Jean's second litter was a challenge, especially for the venerable sow, but also for our staff, who watched with great anticipation. Two days ago, the sow's vulva was enlarged, her teats swollen with milk, and she had ceased to eat—all of which should have been signs that delivery was imminent—but no piglets came. Her breathing was heavy, and she alternated between treading slowly about the yard and resting in her pen. Finally, as the time of birth drew nearer, she took to staying in her pen full-time. On her side she lay, under the heat lamp. And still we waited. She returned to eating, in small amounts. And we listened to her deep breathing, and waited.

And in the morning, we looked in her pen and saw two pigs, one large, and one quite small. A female piglet, of perhaps five pounds, scampered about her 400 pound mother. The little one was covered mucus and blood, and a severed umbilical cord trailed behind her. She stumbled about, rapidly learning the use of her four limbs, and sniffed and felt with her nose, to gain understanding of her new world. Central in this world was her mother. The baby sniffed and felt about the mother's stomach, legs, head, vulva. She suckled at the air, and various places on the mother, in search of sustenance. After more exploring, the piglet discovered what it sought, the mother's teat, and she drank briefly, continued her exploration, ever-curious. She returned to the teats, and suckled more.

Laura Jean's previous litter had six piglets. A sow of Laura Jeans's breed (the large black) can give birth to up to thirteen. Typically, they are 20-30 minutes apart. Two hours after the birth of the first piglet, Laura Jean still lay on her side, her breathing heavy, her body periodically shook with labor. But the second piglet was conspicuously absent. This situation caught the attention of our educational and agricultural staff, which includes our leader Margaret, Hannah, Betsey, Peter, Caitlin, and myself. Captivated by the hog pen, we could only depart for essential duties. I spent the afternoon going back and forth from the hog pen to the office, where I used my graphics skills to assist Margaret with the maps and visuals for a grant proposal concerning a new greenhouse, which was due at the end of the workday.

We called the vet about the overdue piglets. He suspected that the second piglet was turned laterally in the womb. He gave instructions to correct the situation. We persuaded Laura Jean to stand for a moment. Margaret donned gloves, and reached inside the mother pig. Carefully, she had to go elbow-deep. She felt many feet within the womb, many babies. The front infant had indeed turned sideways. I stood at Laura Jean's head, tried to pet and reassure her—she was obviously distressed by the whole affair. Margaret reoriented the piglet. Shortly thereafter, it emerged from Laura Jean, feet first. This young male joined his sister, scampered back and forth and investigated the great mass of flesh that was their key to survival.

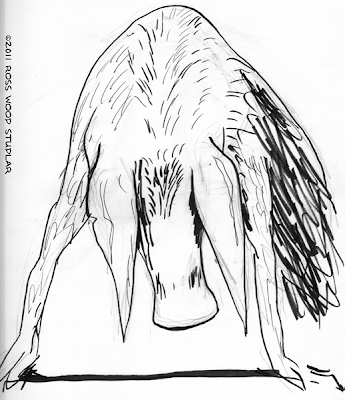

It seems that Laura Jean's trial would not end. She lay on her side, her nose mashed against the side of her pen. Uncomfortable, it would seem, but unnoticed next to her other stresses. She rode the earthquakes and the plagues and the agony of her own biological machinery. Such are the perils of live birth, the mammalian burden. We wished her luck, and brought what assistance we could.

The vet said that we should get Laura Jean to stand on her four feet, that it might encourage the next birth. By now, however, the sow was rather committed to stay lying on her side. We positioned four ranch hands around her. I took the central position, squatted low beside the sow's belly, and reached across her and took hold along her back. The others said that our goal was to encourage her to stand, not to physically move her, so great was her size. I, however, considered it fine challenge to see if I could physically lift and “roll” her to a standing position. On the count of three, we heaved. We managed to rotate her toward me a bit, a little closer to a standing position—and out popped a piglet! My colleagues congratulated me, gave me credit for this third challenging baby. I do not know whether our efforts prompted the birth, or if the timing was coincidental. In any case, I triumphantly exited the pen, with the mother's milk on my boot.

She labored on, and more piglets came. Slowly, sometimes more than an hour apart, but they came. A fourth piglet, then a fifth and a six. Hannah got us started tossing the football in the yard, as we played the role of 'anxious dads.'

The vet paid us a visit, with a shot of oxytocin for Laura Jean. By bedtime, nine babies nursed at her side, climbed on and around her and over each other. He advised us to check on the sow every hour, assist with delivery if needed, and provide a second dosage of the hormone if need be. I got the one AM shift. I awoke to my alarm, disoriented. I made it to the pen. I sat and spoke to the twitching, heavy-breathing pig, petted her sandpaper flesh. I counted the piglets. Ten. I counted twice more—ten still. Laura Jean's labor had not ended, but it was now for the afterbirth. I sat with the mother for some while, then returned to bed, for it would soon be my successor's turn.

Upon returning inside, I saw a note that I was supposed to see before I went outside. It had the updates from Hannah then Caitlin when they checked the embattled sow, a sort of hourly journal. And another dose oxycotin was there, in case needed. As it was already 1:45, I left the decision to my successor as to whether more drugs would help the pig. I returned to bed, and Betsey soon awoke for the 2 AM shift.

Morning. The sun bright. Ten piglets suckled at Laura Jean's side. She was alive, healthy, if a bit weary. The heroic mother. Although there were only ten piglets, her work was comparable to the twelve labors of Hercules. (Perhaps the afterbirth and piglet-raising were labors eleven and twelve?)

Fifth graders from Rifle Middle School came to visit the Ranch that day. They were enamored with the babies, as we all are. Near the end of the field trip, Hannah and a class chanced upon tragedy. A piglet lay on its side, motionless.

Laura Jean, being a pig, is a devoted and careful mother. She treads with caution about her young. She goes from standing to lying on her side and back again, giving the piglets signals to clear, and keeping her movements wary. Alas, the early hours of life are dangerous for the young. Their mother is groggy, and they are new to the world. And hence, this unfortunate boy piglet—with crease marks on his head from where his mother had crushed him.

Birth and death are common on the ranch. We had lost a chicken to a raccoon earlier in the week, and had lost two pigs for sausage and ham. Typically, animal remains go to the “bone yard,” and become food for ravens. But this instance was special. So much effort to bring the new piglet into the world, so much vivacity and cuteness—to end so prematurely. Peter lifted the piglet with a spade. To the boneyard we went, the five educators and ranch hands.

We couldn't let the ravens have this piglet; it seemed undignified. And so Peter started a hole, next to a cottonwood tree. I took my turn at the dig. Perhaps a foot square. In went the limp piglet. We covered him, and placed a pile of large rocks atop, to mark and protect the grave.

We each took a turn saying or singing a word for the piglet. Hannah sang “I Say a Little Prayer” by Arethra Franklin. I spoke a few words from the book of Ecclesiastes: “All go unto one place; all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again.” Peter said he was glad that the tree would absorb the nutrients. And we left the piglet to return to the soil.

Several days later, we lost another piglet. She was wounded in the midsection, cause uncertain.

The eight siblings remain alive and vivacious. Eighty per cent is an excellent survival rate, in the dangerous world that baby animals inhabit. The piglets drink mother's milk, and follow her about the lush green pasture, against the backdrop of Basalt Mountain. It is spring—herons fly overhead and Canada goose parents lead their goslings about the pond. It is spring, and Rock Bottom Ranch is full of life.