It can be demoralizing, that in so idealistic a city as

Portland, Oregon, there are still so many people sleeping in doorways and begging for change. And the number has increased significantly in the past year. It is a dark side to Portland's status as a happening place, and the mass migration of people (including many young seekers and professionals) to the west coast. As cities like Seattle, Portland, and San Fransisco grow in population, housing prices go up, and the poor folk are priced out, to go sleep on park benches and shiver through the rain.

In Portland, rents went up by more than 15 per cent in the past year, while most people still make less money than they did before the Great Recession. Capitalism is a brutal game.

(While I was working on this blog entry, the state of Oregon passed legislation to raise its minimum wage, which is an important first step to remedy the situation.)

Although we may not be homeless in the streets yet (in many cases saved by our parents), many people in my "Millennium" generation have been stung by the scorpion of this fierce and rigged economy.

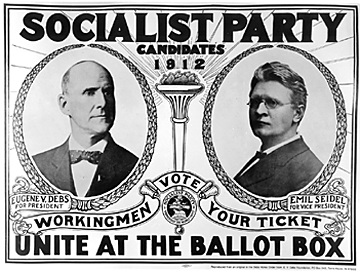

(In one dramatic example, A Yelp! [$1.37 billion company] employee was forced to live off of brown rice and with no heat, thanks to low pay and high rent in San Fransisco. When she shared the truth on her blog, they fired her.) Maybe that's why we are willing to consider progressive reforms from a true visionary. Today, we have a socialist candidate with a chance of winning the Democratic nomination!

Bernie Sanders has gone from protest candidate to real candidate with amazing rapidity. Although Bernie calls himself a Democratic Socialist,

Noam Chomsky describes him as a

decent and honest New Deal Democrat. Many of the programs Sanders proposes, such as universal health care and tuition-free college, already exist in much of the developed world. Only the highly conservative political atmosphere of the United States (where Republicans are far right and Democrats are right-of-center) are his plans perceived as extreme left.

In times like these, we should revisit and remember the literary work of another noted American Socialist and visionary…..

Jack London! Today, most people associate London (who lived from 1876-1916) with only a fraction of his literary accomplishments. While his stories about struggle and survival in the Klondike (e.g.

The Call of the Wild,

White Fang, and "To Build a Fire") are significant, Jack also did so much more…. He wrote over 50 books, including novels and collections of essays and short stories, in settings ranging from the South Pacific seas to a post-apocalyptic San Francisco. He was a pioneer of science fiction, worthy of placement on the same bookshelf as

Jules Verne and

H.G. Wells. Jack was quite attached to the symbol of the wolf (and was himself nicknamed "Wolf" by friends) and intrigued by the power and violence of nature. However, at heart, Jack was more of a sociopolitical writer than a nature writer, with the call for a socialist revolution to save people from poverty and injustice driving his pen across paper. He ran for mayor of

Oakland, California on the Socialist Party ticket twice.

Like many kids, I thrilled to Jack's Klondike stories. I began to discover his broader scope of work when I was sixteen, and saw

The Star Rover on the shelf at the public library of Morgantown, West Virginia. I read the tome, and was awestruck. From there, I started trying to read all of Jack's books. (Maybe someday, I will complete that project.)

The Road is a great one to read aloud by the fireside. In the first chapter "Confession," a teenage boy wanders the streets and bangs on doors. After instantly "sizing-up" the respondent, he invents a story--often purporting himself as an orphan on a trek to meet his big sister and her family, with many variations--as means of clutching hold of their heart-strings and procuring food hand-outs. The boy is Jack London, who notes that

"to this training Of my tramp days is due much of my success as a story-writer." In the next chapter "Holding Her Down," Jack freeloads on trains for cross-continental travel, and performs death-defying feats of athleticism in evading the guards who seek to throw him off. In subsequent chapters, Jack describes his horrific time in prison for vagrancy--the experience which led him to turn to socialism, as well as pursue an education and a writing career.

After his prison stint, Jack returned home to Oakland, crammed the contents of four years of high school into one-and-a-half years of intensive study, did well on standardized tests and was accepted into the University of California at Berkeley, did not graduate, and went on more adventures such as gold-prospecting the Yukon. He submitted many manuscripts to literary magazine, taking artistic and philosophic inspiration from Rudyard Kipling, Edgar Allan Poe, Karl Marx, Charles Darwin, Friedrich Nietzsche, and above all his own life experience. His first pro sale was the science fiction short story "One Thousand Deaths" to

The Black Cat. His big breakthrough was his second novel, the overnight bestseller

The Call of the Wild, published in 1903. This work catapulted Jack from obscure scribe to international celebrity. From then until his untimely death in 1916, he received pay and fame for his writing comparable to today's Hollywood actors.

Jack could describe a fight with primal force. The boxing match described in his short story

"A Piece of Steak" stays with me as though I had both seen in on a giant IMAX screen, and experienced it in real life, at the same time. In his sociological science fiction novel

The Iron Heel, Jack brings forth the same primal force to describe heated debates between his working-class socialist hero Ernest Everhard, and the businessmen and academics who expunge the merits of capitalism. Ernest is a charismatic warrior, who wins people from both the streets and the lecture halls to his cause. And he wins the heart of Avis Cunningham Everhard (who narrates the novel.) Ernest leads a socialist revolution, but the Oligarchs crush it, leading to a nightmare future, under the Iron Heel. Avis Everhard ends her narration in mid-sentence and hides her manuscript in an oak tree when the fascists come to take her away. 700 years later, after many more failed attempts, the socialist revolution succeeds, leading to "The Brotherhood of Man." And as luck would have it, someone discovers the Everhard text. A future scholar attaches numerous footnotes to give context to his audience. In 1907, this was a very unusual structure for a novel! Today, we have seen many works of science fiction and speculative fiction that use fake documents to lend credibility and believably to the imaginary world--

Watchmen,

Foundation,

The Handmaid's Tale,

Unstable Molecules,

The Massive, and

Tarzan Alive!, to name a few.

War with the Newts by Karl Kapek was an early example of this technique. And London's work was earlier.

Furthermore,

The Iron Heel (1907) is the first of the modern dystopian novels, predating

1984 (1947),

Brave New World (1931), and

Fahrenheit 451(1953) by decades. And certainly predating

We by Yevgeny Zamyatin (1921), which is sometimes erroneously credited as the first dystopian novel.

George Orwell acknowledged that he took a great deal of inspiration from Jack London, and that

The Iron Heel had a direct influence on the later and better-known dark vision of the future.

Inevitably, readers of

The Iron Heel will see parallels with their own contemporary times, whether its the 1980s or 2010s. The connections are as obvious today as ever, as a Democratic Socialist (Sanders) faces off against an opponent who is basically a Fascist (Trump) for the office of president. Movements like

Occupy Wall Street and the

Fight for Fifteen are reminiscent of the worker's revolution which Jack London hoped and fought for.

In the penultimate year of his short life, Jack London finally wrote the book he had been reaching for since the day he decided to become a writer:

The Star Rover. While

The Road succeeded resoundingly as an adventure story, it did not fully deliver on communicating the social evils Jack saw and experienced as a prisoner. In

The Star Rover, Jack more powerfully describes the hell of prison at the turn of the century. His protagonist Darrell Standing is partly based on the real San Quentin survivor

Ed Morrell, who had been a guest of honor at Jack London's ranch. In a mix of fact and fiction, London includes Morrell as a character too, who talks to Standing by tapping messages in Morse code, across the walls of their prison cells. Locked in solitary confinement and tortured by means of a straight jacket that produces angina, Standing learns the art of astral projection….. and his spirit escapes to wander the stars! He returns to past lives and lives them again, as a rapier-duelist, a seal-hunting sailor, a Chinese nobleman, and a witness to the crucifixion of Jesus. I cannot put into words the effect that this work had on me when I first read it, the power and wonder and fear and dread of it all. Curiously, most readers in Jack London's own time felt differently--

The Star Rover was met with low sales and denunciations from critics, and was overall the least popular of all London's books. (Although it was still made into a silent movie in 1920.) The tome has enjoyed a revival in recent decades, with printed additions by publishers ranging from Prometheus Books to Valley of the Sun, with accompanying interpretations by the reincarnation researcher Dick Sulphem and the literary scholar Leslie Fiedler. It was a book ahead of its time. It is uncertain whether Jack London really believed in reincarnation, but it's fiction--George Lucas is not obligated to believe in the force.

By my senior year of high school, Jack London had become much more than the topic of my final project in English class. He was a literary hero of mine. I too hoped to be an adventurer and storyteller (through both words and pictures--comics--in my case), and to fight for marginalized beings (in my case, I was especially concerned with animals and plants, Mother Earth's world.) And I am not the only Studlar upon whom Jack's work had a profound effect. My big brother Carl was attending Wittenberg University when I was still at Morgantown High School, and when he came home for Christmas Break, he caught hold of my library copy of

The Star Rover. He too was left in awe, and he too was soon reading more of Jack's work. This fueled a yearning he had been developing to go out and experience true adventure. To escape the sanitized and protected world that privileged people inhabit, and not just to climb rocks with the high tech gear. Eventually, he found the adventure he sought by joining the Peace Corps, and served for two and a half years in rural El Salvador. He survived amoebas and parasites, and left his village

El Matazano with many improvements, including a computer lab at the public school, to prepare students for work and life in a high-tech world.

Today, our world evolves rapidly. I too can be affrighted by new online worlds and forms of virtual reality, and how they will change the direction of ourselves and our society. However, one thing is clear. Older forms of virtual realty--in this case, prose--continue to affect and direct what we do in the real world!

***********

Recommended:

"Jack London and Science Fiction" by Clarice Stasz

Review of The Iron Heel by Ben Granger, Spike Magazine

Because Jack London has been deceased for over 70 years, his entire body of work is in the public domain and can be freely copied and shared. Some of his works can be found here. Or if you're like me and you like paper, visit a public library.

The photos and book covers are also in the public domain, with the trains image in the Library of Congress collection and boxing image from the Imperial War Museum.

No comments:

Post a Comment